Acute Surgical Wounds Part II: Steps to Create an Acute Surgical Wound Service for Your Facility

July 18, 2019

In 2010, Christiana Care Health System, a 1,000 bed Level I trauma center in Newark, Delaware, introduced an acute surgical wound service (ASWS) integration plan with a single dedicated nurse practitioner, trauma surgeon, and administrative leader. Subsequently, trauma patients with complex wounds experienced decreased morbidity and length of stay. Closely aligned with these numbers, their patient days of negative pressure wound therapy fell from 11+ days in 2010 to 8.2 days in 2018, representing one of the lowest in the nation. As described in part 1 of this blog series, an ASWS is an amalgamation of an acute surgical wound service, providing a multidisciplinary, comprehensive approach to optimize healing of acute wounds and reducing facility costs.

While meeting organizational, provider, and patient needs, the suggested augmentation does not reduce utilization of other associated hospital services, but rather unifies the efforts. With 67% of our trauma patients having acute wounds, yet avoiding chronicity, our ASWS successes have brought inquiries from other facilities regarding how they might create a similar service.

The following is a basic outline for an ASWS integration plan, not all encompassing, and therefore open to any adaptations.

Indications for ASWS

- Need for specialized, individualized patient care to optimize outcomes

- Need for coordination of care from inpatient to the operating room to outpatient settings

- Need for improved communication among health care providers, caregivers, and patients

- Need for increased awareness and incorporation of evidence-based recommendations

- Need to enhance surgical residents' training (Few hours are currently dedicated to wound care in medical school. We applaud those who have established wound care–specific clinical fellowships within their medical schools.)

- Need for standardization of advanced wound management

- Need to reduce length of stay, visits to operating room, readmissions, emergency department visits, and time to wound closure

Collateral benefits

- Wound specialists have experience and training to evaluate and treat patients independently while the surgeon is performing other procedures.

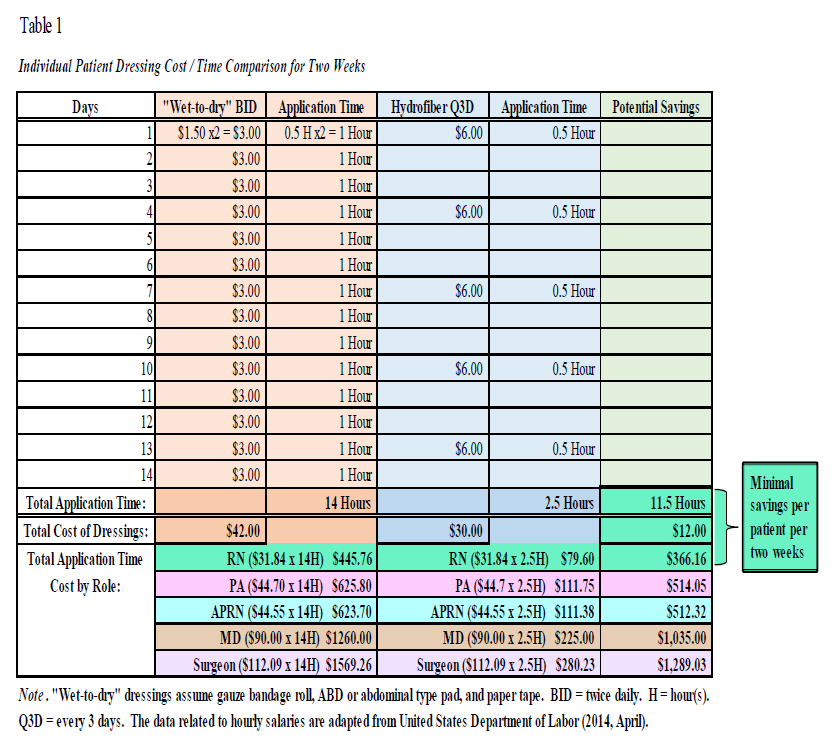

- It saves nurses' and other providers' time and cost of wound care because of decreased frequency of dressing changes with advanced multiday dressings.

Considerations

- An ASWS will not initially have adequate staffing to cover weekends and off-shifts. (However, if it is a teaching facility, residents gain an opportunity to become knowledgeable and improve their wound management skills to extend the service.)

- Time and education will be necessary for transformation of common misconceptions to adoption of preferred wound care methods.

- Wet-to-dry should not be the go-to dressing for all wounds.

- Allowing wounds to scab can conceal collections and infections, increase pain, prolong healing, and worsen scarring.

- Silver sulfadiazine is not the dressing of choice for burns.

- Advanced wound therapies are not necessarily more costly (see Table 1).

Strategic planning

- Gain support from facility leaders.

- Active involvement of a key surgeon and a prominent administrator is essential.

- Recognition of the service's value by other key persons is advantageous for growth.

- Surgeons: trauma, vascular, plastic, infectious disease, general, orthopedic, emergency department

- Administrators

- Patient safety professionals

- Performance improvement professionals

- Case managers

- Nursing leaders

- Hospitalists

- Establish partnerships.

- Community

- Wound care centers

- Home wound care delivery vendors

- Vendor representatives

- Physical therapy and occupational therapy

- Home care providers

- Skilled nursing facilities

- Rehabilitation facilities

Our Successful Integration of an Acute Surgical Wound Service

A prominent administrative leader and a trauma surgeon recognized the need for improvement in providing a continuum of high-quality care among severely wounded patients. I fulfilled the role of lead nurse practitioner with the newly designed ASWS at our facility. I spent 10 months being trained 1:1 by the trauma surgeon and seeing patients at the bedside, in the operating room, and in the outpatient setting. My first patient met criteria for a below-the-knee amputation, but instead we implemented evidence-based practice, advanced wound care, and close follow-up, augmented by his and his wife's attitude "to do whatever was necessary to save his leg." Recently I saw him, walking in on two healthy legs, to visit a patient in the hospital.

As coworkers witnessed such success stories, an initial ASWS census of 17 patients quickly grew to consultations for over 300 patients seen by our ASWS. It was a huge benefit to have an existing, well-established wound, ostomy, and continence nursing department comprising nurses who predominantly cared for patients with chronic wounds, pressure injuries, and stomas. Therefore, available wound care dressing supplies were largely associated with those needs. Although multiple vendors approached us with their novel dressings, expedient healing was achieved by frequent debridement combined with a few advanced wound care therapies. Additionally, we reviewed the hospital formulary to determine whether any existing dressing products could be utilized. As with most institutions, to seek approval for other specific wound care items we had to present outcomes, cost analyses, and pertinent research to the new product committee. Our preparedness, enthusiasm, and before/after wound photographs gained approval as we acquired an arsenal to prevent acute wounds from becoming chronic.

Any spare time was devoted to wound-related research, which resulted in two journal publications by the following year that continue to receive scholarly citations.1,2 Concurrently, we gave presentations within the institution to provide education regarding the availability of the new service, implementation of advanced wound care ideologies, and the potential advantages. Vendors of most wound care products promised to provide education, so we accepted those offers to benefit surgical-medical residents and nurses throughout the hospital system. We sought wound care certification and, later, wound specialist certification while attending wound care conferences to keep informed of the latest evidence-based and experiential practice. These conferences afforded us opportunities to share our accomplishments.

Conclusion

Our ASWS model and the broad outline provided here can be adapted to any surgical facility. The next ASWS blog topic will be: Creating a custom interactive website resource for your facility.

References

1. Shweiki E, Gallagher KE. Negative pressure wound therapy in acute, contaminated wounds: documenting its safety and efficacy to support current global practice. Int Wound J. 2013;10(1):13-43.

2. Shweiki E, Gallagher KE. (2013, September). Assessing a safe interval for subsequent negative pressure wound therapy change after initial placement in acute, contaminated wounds. Wounds. 2013;25(9):263-271.

3. Gallagher KE. Utility of web-based support for acute surgical wound care. 2016. (ProQuest no.10012944).

4. United States Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics: National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates United States. Washington, DC: United States Department of Labor; 2014.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely those of the author, and do not represent the views of WoundSource, HMP Global, its affiliates, or subsidiary companies.